The importance of journalism was reinforced to me last week when I came across the headline: “Hands of my health records, in the name of privacy” (The Australian, July 18).

The headline was catchy, I am concerned with privacy and I do enjoy author Janet Albrechtsen’s writing so I forged ahead.

A new government initiative, My Health Record, was recently created to centralise citizen’s health records for the purpose of ‘efficiency’ and ‘improved patient welfare,’ and some other buzzwords most likely.

The catch is that one has to opt-out if you do not wish to be placed into this government database or as I call it: the data deathbank.

If the MHR was so great, like all government projects, surely we would all opt-in.

This line of reasoning may indicate that the government is aware of the issues with the MHR (numerous), but none so great as the potential for sensitive information to be accessed by someone, or some groups, who should not be within cooee of it.

The first I heard of the MHR was Albrechtsen’s article. Once completed, I went online and opted-out immediately.

You see the government did not spend much on a public campaign to try to sell their new scheme. Surely if I am being signed up to something I have the right to know what it is.

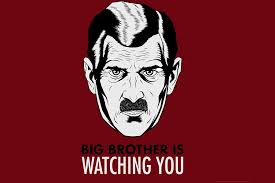

Peter Van Onselen (The Weekend Australian, July 21) appropriately described the scheme as Orwellian.

In an era of hackers, leaks and gross privacy negligence, only schmucks would trust their private information to a data deathbank.

To think the government has a better chance of securing private data if targeted by someone or a state like China or Russia with the means to get in and out without detection is naïve.

To paraphrase former FBI Director James Comey: “There are governments who have been hacked and there are governments who don’t know they’ve been hacked.”

The lack of public campaigning from the government indicates they are aware of the grotesqueness of gathering data on people, even if disguised by the name of healthcare.

In theory, the MHR may have been a good thing. In practise, it is too big and idealistic its pitfalls are glaring.

Consider the fact that the Australian Medical Association conducted a survey of doctors of which 76% of respondents were sceptical the MHR would have any benefit to patients.

The survey also found that the potential for gross misuse was high as, for example, access to sensitive information is open to admin officers (who aren’t health professionals).

The whole concept is ridiculous and illiberal.

For the Liberal Party to introduce the MHR and then try to sneak this past Australians is contemptible. In this case, the Liberal Party was liberal with your information but not the truth and shunned the principles of liberalism.

Thankfully, these journalists have not cast aside the importance of privacy.